- Home

- Kelley Armstrong

The Unquiet past Page 2

The Unquiet past Read online

Page 2

I’m a foreign princess, locked away here to keep me safe until I’m eighteen.

I’m the child of international spies, who feared for my life and will come for me when it’s safe.

I’m an alien, beamed down to Earth until my eighteenth birthday, when my programming will trigger and I’ll take over the world, mwa-ha-ha.

Admittedly, that last one was Tess’s. It made the other girls laugh and tell her she was crazy.

Crazy.

Even thinking that made her stomach clench. A word shouldn’t have such power. She’d tried to rob it of that power by courting it. She’d do and say outrageous things, and the other girls would call her crazy, and she’d be fine with it, because it wasn’t the bad kind of madness. The kind she feared. The kind that nudged at her when she awoke from her dreams. The kind that dug its claws into her back when she saw…what she saw.

That was the answer she wanted. Why did she have the dreams? Why did she have the…rest? Where did they come from? Did they make her crazy? Would they make her crazy eventually?

She clutched the box tighter. Forget that for now. Forget answers. There was something else in here she craved almost as much.

Adventure.

The box would not contain anything as prosaic as a name. She’d read enough books to know that. If someone, her mother, perhaps—even thinking the word made her heart beat faster. No, a mother was too much to hope for. Someone then. If someone had a name to give her, it would come in an envelope.

A box meant a clue. The beginning of an adventure. It would be a key to an old train-station locker. Or a lock of hair, tied with a special ribbon only sold in one place. Or a wedding ring engraved with initials and a date. A clue that would set her on the path. To answers. To adventure.

She smiled, and by the time she got the lid off, that smile had turned to a grin.

Answers and an adventure. What more could she want?

Inside was a faded pink satin pouch. One that could easily hold a key or hair or a ring. She felt the pouch. Something within crinkled. She prodded and rubbed at it. More crinkling.

Tess undid the ribbon, reached in and pulled out a folded piece of paper. On it was…

An address and a phone number.

That was almost as disappointing as a name.

She shook herself sharply. Disappointing? It was an address. And a phone number. A direct link to her past. Did she really want it to be more difficult?

She swallowed. Yes, perhaps she did. She wanted to earn her answers. To set off on an adventure and prove herself worthy of them, like the characters in her books. Except most of those bold adventurers were boys. Maybe this was how the universe worked for girls.

No, girls might have a tougher time striking out on adventures, but it certainly could be done, and it was foolish to think that the universe conspired to keep them safely ensconced in their little homes and towns.

She smoothed out the paper with the phone number and address. It threatened to crack at the lines where it had been folded. Old paper. Fourteen years old now. Probably fifteen, actually. She’d come to the Home when she was just over two. Some girls who’d arrived at that age still had memories of their childhood. Tess did not. Just dreams. Dreams she prayed had nothing to do with her former life.

She didn’t recognize the area code of the phone number. Her gaze traveled to the address: 16532 Rue Montcalm, Sainte-Suzanne, Quebec.

Quebec? They’d had a French teacher who’d sworn Tess was French because of her dark hair and dark eyes and Therese as her full name. Mrs. Hazelton had told Tess not to pay her any mind, but ever since Tess had given particular attention to her French lessons and made sure she got the best marks in class.

If this was her home address, then she really was French. A French Canadian. Even thinking that made her feel a little more whole, a little more real. Not just an orphan girl, but a French orphan girl from Quebec. When you knew nothing about yourself, every scrap that said “this is who I am” was enormous. And here, with this address and this phone number, Tess might have more than a scrap. Much more.

She tucked the note back into the pouch and ran off to find the matron.

Mrs. Hazelton was a popular person today. Tess impatiently waited to see her again.

“I got a phone number,” Tess said as she walked in. “And an address.”

“I suppose you want to try it?”

Tess nodded.

Mrs. Hazelton pushed the phone toward her. “I’d offer, but I’m sure you’d like to do the honors. You need to dial 1 first, for long distance.”

The matron knew it wouldn’t be local then? Tess supposed Mrs. Hazelton had always known a little more than she’d let on. That wasn’t cruelty—it was understanding that those scraps of identity, however treasured, were like finding a single coin from a buried treasure. One coin seemed like a fortune…until you realized how many more there were, and then suddenly you weren’t satisfied with one anymore, and eventually you might even wish you’d never found it, because it only made you greedy for more.

Before Tess could start dialing, Mrs. Hazelton said, “I should warn you…” Then she trailed off and shook her head. “Go on.”

Tess dialed the number. She expected her fingers to shake. They didn’t. They turned the dial with calm precision. The answers were near. No need to rush now. Just prepare.

She did hold her breath as the line connected. Then, when it clicked, a cold wave of panic seized her.

What would she say? What was she supposed to say? She should have planned—

A voice came on the line, speaking French in a slow, measured tone, easy for Tess to decipher.

“Quel numéro demandez-vous?” What number are you calling?

It was the operator. Tess struggled for a response.

“Je voudrais...le—”

“Parlez-vous Anglais?” Do you speak English?

Tess exhaled with relief. This wasn’t the time to test her French.

“I do,” she said. “The number I called was…” She rattled it off.

The operator had her repeat it and then said, “That number is no longer in service.”

“Is there a, uh, forwarding number?”

“We do not do that, mademoiselle. Do you have a name and address?”

“An address.”

“I will require a name as well.”

Tess hesitated. She’d been about to give her surname—Stacy—when she remembered it wasn’t hers at all but a name the matron had given her.

“Just a moment,” Tess said. Then she remembered to add, “Please.” She covered the receiver. “They need a name with the address. If it’s someone from my family, my real name would help.”

Mrs. Hazelton’s blue eyes clouded with sympathy. “I don’t know it. Here, let me speak to her.” She took the phone and slid into her “outside” voice—the one she used with tradespeople and such. “This is Mrs. Agnes Hazelton, matron of the Benevolent Home for Necessitous Girls in Hope, Ontario. The young woman you were speaking to is one of our wards. She has a phone number and address that may provide some insight into her family history. Is there anything you can do for her?”

A short pause, then the matron gave the number and address. Another pause. Then, “I see,” and “Yes,” and “Of course,” and “No, I understand.” With the last one, something inside Tess crumpled. Her knees threatened to crumple as well, and she had to put her hand on the desk to keep steady. Mrs. Hazelton thanked the operator with a sincere “Merci beaucoup” and hung up.

“She couldn’t help, could she?” Tess said.

“I was going to warn you that the number might not work. It’s been almost fifteen years, Therese. Perhaps I ought to have said something, but…” She shook her head. “The operator did check the address. It’s a small town, so it wasn’t difficult. There isn’t a telephone number listed for it. That’s not unusual, she said. It’s rural Quebec, north of Montreal. Not everyone has a telephone. As for the number, she could only

tell me that it’s been disconnected. There’s no way of knowing if it was attached to that house beforehand or if it’s passed through a few since. The important thing, then, is the address.”

Tess looked down at the black lines swimming on the paper; her eyes had misted without her realizing it.

“You think I should…I should go there?”

To Quebec. Take the train to Montreal. Hope to Toronto to Montreal—Tess knew the route, had dreamed of riding it someday.

An adventure. She was about to get her adventure.

And what did she feel? Terror. Bubbling up from that part of her that thought, Me? I’m only sixteen. I’ve never even been to Toronto, and now I’ll go to Quebec on my own? Find this house on my own?

Even as that panicked voice inside her said the words, she felt something else. A slow, delicious thrill—half fear and half excitement.

She was almost seventeen. Old enough to travel in the world by herself. There were girls younger than her in town who’d quit school and gone down to Toronto to become hairdressers or nannies.

“I think you’re ready, Therese,” the matron said with a small smile. “Don’t you?”

Tess nodded.

Thanks to the fire, there wasn’t much to pack.

Thanks to the fire.

She would never be grateful for the total destruction of her home and belongings, but mingled with her grief was an odd sense of lightness. Of freedom. Terrifying freedom, setting out with little more than the proverbial clothes on her back. But perhaps, in some ways, that made it easier. All her life, she’d dreamed of the day she would head off to Toronto. No disrespect—or lack of love—toward Mrs. Hazelton and the other girls. There would be tearful farewells, but she’d still take the first train out of Hope.

Now that day was here, and she couldn’t help but wonder, if it had simply been her eighteenth birthday, would she have gotten on that train? Eventually, yes. But perhaps not immediately. Without something spurring her on, she might have found reasons to linger a few days. This was her home. This was her family. It could not be cheerfully thrown off like a winter coat on the first day of spring.

But with the address, she had a purpose. A reason to leave. And with the fire, she had no reason to stay. She had only one change of donated clothing to stuff into a donated bag, and she would discard both as soon as she could. As charity offerings went, these came from the bottom of the barrel—or a smelly storage bin. Ten years out of date, a couple of sizes too big, hanging off her tiny frame. To call them “well-worn” allowed them a courtesy they did not deserve.

No matter. She was going to Montreal. There was no more fashionable place in the country, perhaps on the continent. She was a French girl now, and she would dress like a French girl. Miniskirt and knee-high boots were only a day’s train ride away.

Three

TESS WAS GOING to Montreal. Yes, it was only a stopover, but that was where her train journey would end. In the city of a hundred bell towers, as Mark Twain had called it. That’s how she’d always pictured it: a metropolis of soaring towers and sonorous bells.

Billy leaned over as they waited for the train. “You look as if you’d travel the whole way with your nose out the window, like our dog heading to the beach.”

She grinned. “I would, but I don’t think the train windows open.”

He gave her a brief, fierce hug. “I won’t say I’ll miss you or this will become a very sappy goodbye. But I’m going to give you this.” He pressed a ten-dollar bill into her hand.

“I don’t need—”

“I know. You have almost $140 from the matron and another $200 from your savings. You could buy an old car with that. That $10 is to be used for one purpose: phoning me. Yes, we agreed mail was cheaper, and I’ll still expect letters, but I want calls too, and if I’ve given you money for that, you’ll feel honor-bound to use it.”

“Letters would be fine,” she said. “The postmistress will see them, and you know what a gossip she is. As long as I’m writing, she’ll tell everyone we’re still together.”

He gave her a stern look. “That’s the last thing on my mind, Tess. I want you to call because I want to talk to you. You’ll want to talk too, but you hate spending money.”

“All right.” She folded the bill and put it in a special compartment in her donated purse. “I’ll phone every third day.”

“Starting at the train station in Montreal.”

She smiled. “Yes, sir.”

“Hold on.” He walked back to his parents’ Ford Fairlane. When he returned, he was pulling a bright-purple suitcase.

“It was Suze’s. She outgrew purple.” He set the suitcase on its side and opened it. Inside was some carefully packed clothing. “She outgrew all this too, so Mom told me to give it to you. It’s not exactly the height of fashion…”

“It’s perfect.” She threw her arms around his neck and whispered, “Thank you.”

When she pulled back, he was blushing. The other people on the station platform smiled at them. The train whistle sounded, and when she squinted against the sun, she could see the train rumbling down the tracks.

“There’s one more thing,” Billy said. “Your birthday present. I hope I’ll see you again before that, but you can use them now.”

He dug to the bottom of the case and pulled out a pair of boots. They were black vinyl, knee high, with low heels and a zipper up the back. Tess let out a shriek.

Billy laughed. “I don’t think I’ve ever heard you do that. Good choice?”

“The best. Oh my god.” She caught a couple of less-indulgent looks from adults nearby and amended it to, “Oh my gosh.”

“I picked them up in Toronto last month. I hope they fit.”

Tess was already out of her Oxfords and pulling the boots on. They did fit. Well enough anyway. She gave him another hug as the train pulled into the station.

“You’ll call,” he said.

“And write.”

“And come back,” he said. “Not to stay.” He met her gaze. “I don’t ever expect you to stay, Tess. But I wouldn’t want to think I won’t see you again.”

“You will. Promise.” One last hug, with a peck on the cheek, and he helped her stuff the few belongings she needed into her new suitcase. Then he took the donated bag with the donated clothing and whispered a promise to make it disappear. One last hug, and she was off, climbing the steps onto the train, purple suitcase in tow, trying hard not to stumble in her new boots.

It was a relatively short trip to Toronto, or so other people on the train said. Short for experienced travelers. Long for those who’d never been more than twenty minutes out of town. Endless for a girl straining for her first sight of a big city.

Perhaps it wasn’t actually her first sight. She might have been this way before, as a toddler on her way to Hope. Maybe she’d spent time in Montreal. She might have even lived there.

Exciting thoughts. Confusing thoughts. She was used to them, though, that disconcerting feeling that came with knowing you’d lived another life, one you couldn’t remember. Almost like being reincarnated. I used to be someone else. Live somewhere else. Answer to a different name.

She wouldn’t think of that right now. She’d think of Toronto. Of two hours to venture from the train station and see the city before making her connection to Montreal. Billy had said the station was right downtown, near lots of things to see and do. He’d suggested she might want to shop, but he’d been joking. She was frugal enough to restrict herself to window-shopping…at least, until she reached Montreal.

When the train finally arrived in Toronto, there was a moment, standing in the cavernous station, when a cowardly little part of her whispered that maybe she should just find the departure gate and wait. She squelched the voice with one squeak of her new boots, turning sharply and marching to the front doors, walking out into…

She would say she walked out into sunshine, and she did, but what she saw first were the buildings. Soaring buildings everywh

ere. They should have blocked the sun, but somehow it still shone, warming the endless pavement.

She’d never seen so much pavement. That’s all there was, no matter which direction she looked. Pavement rolling out like gray grass. Buildings so high she had to crane her neck to see them. And the smells. That was, perhaps, the most shocking part of all. The city stunk—of exhaust fumes and baking asphalt and the faintest whiff of smoked meat. Perfume too. So much perfume, bathing her in a cloud of it each time the train-station doors opened and travelers poured out. Tess supposed the smell of it all should make her stomach churn. Instead, it set her pulse racing.

As she turned, she caught sight of one person who didn’t fit the scene. He was dressed oddly, in an old-fashioned vest, and his shirtsleeves rolled up, with a red bandanna around his neck and a flat, shapeless hat on his head. More jarring than his outfit was the fact that he walked in the middle of the road with cars whipping past him, his head bent, as oblivious to the vehicles as they were to him.

A ghost. No, please. Not here. Not now.

“Can I help you, miss?”

Tess spun. A man in a porter’s uniform stood behind her, holding the door for an elderly woman.

“You look lost, miss,” he said. “Can I help?”

Tess didn’t glance back at the man in the road. Not today. There would be none of that today.

She looked at the porter and said, “Do you know where I could get lunch, sir? Before my next train?”

“You shouldn’t go far, miss. If you want something simple, there’s a deli just down the road. If you want fancy…” He motioned across the road, to a grand hotel that sprawled down the whole block. It was the tallest building around, with a beautiful glassed-in roof garden. He lowered his voice. “The tearoom has sandwiches. It’s a proper place for a young lady. Very safe.”

She thanked him and considered her options. Most days, she’d go with simple and inexpensive. Today though…Tess clutched her luggage handle and started across the road.

The Calling

The Calling Darkest Powers Bonus Pack

Darkest Powers Bonus Pack Betrayals

Betrayals Sea of Shadows

Sea of Shadows Rough Justice

Rough Justice This Fallen Prey

This Fallen Prey City of the Lost: Part Five

City of the Lost: Part Five Perfect Victim

Perfect Victim Dime Store Magic

Dime Store Magic Personal Demon

Personal Demon Haunted

Haunted Living With the Dead

Living With the Dead Visions

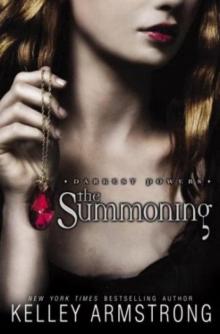

Visions The Summoning

The Summoning Broken

Broken City of the Lost: Part One

City of the Lost: Part One No Humans Involved

No Humans Involved The Awakening

The Awakening The Reckoning

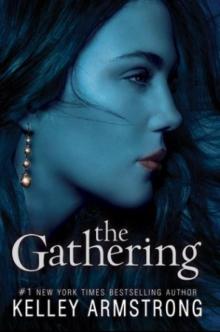

The Reckoning The Gathering

The Gathering Bitten

Bitten Thirteen

Thirteen Gifted

Gifted The Orange Cat and Other Cainsville Tales

The Orange Cat and Other Cainsville Tales Darkest Powers Bonus Pack 2

Darkest Powers Bonus Pack 2 Rituals

Rituals Waking the Witch

Waking the Witch Made to Be Broken

Made to Be Broken Lost Souls

Lost Souls Empire of Night

Empire of Night Wild Justice

Wild Justice Double Play

Double Play Alone in the Wild

Alone in the Wild City of the Lost: Part Two

City of the Lost: Part Two A Stranger in Town

A Stranger in Town Watcher in the Woods: A Rockton Novel

Watcher in the Woods: A Rockton Novel Atoning

Atoning Spellbound

Spellbound Wolf's Bane

Wolf's Bane A Darkness Absolute

A Darkness Absolute Ballgowns & Butterflies: A Stitch in Time Holiday Novella

Ballgowns & Butterflies: A Stitch in Time Holiday Novella Wherever She Goes

Wherever She Goes A Royal Guide to Monster Slaying

A Royal Guide to Monster Slaying Life Is Short and Then You Die

Life Is Short and Then You Die City of the Lost: Part Three

City of the Lost: Part Three Frostbitten

Frostbitten A Stitch in Time

A Stitch in Time Industrial Magic

Industrial Magic Wherever She Goes (ARC)

Wherever She Goes (ARC) Snowstorms & Sleigh Bells: A Stitch in Time holiday novella

Snowstorms & Sleigh Bells: A Stitch in Time holiday novella Exit Strategy

Exit Strategy Forest of Ruin

Forest of Ruin Cursed Luck, Book 1

Cursed Luck, Book 1 The Gryphon's Lair

The Gryphon's Lair City of the Lost

City of the Lost City of the Lost: Part Four

City of the Lost: Part Four Deceptions

Deceptions City of the Lost: Part Six

City of the Lost: Part Six Urban Enemies

Urban Enemies Stolen

Stolen Every Step She Takes

Every Step She Takes Portents

Portents Wolf's Curse

Wolf's Curse The Unquiet past

The Unquiet past Omens ct-1

Omens ct-1 Cruel Fate

Cruel Fate The Calling dr-2

The Calling dr-2 The Awakening dp-2

The Awakening dp-2 Life Is Short and Then You Die_First Encounters With Murder From Mystery Writers of America

Life Is Short and Then You Die_First Encounters With Murder From Mystery Writers of America Goddess of Summer Love: a Cursed Luck novella

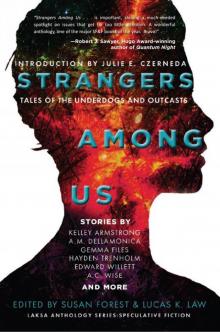

Goddess of Summer Love: a Cursed Luck novella Strangers Among Us

Strangers Among Us The Gathering dr-1

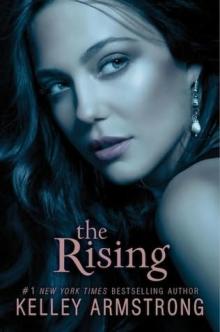

The Gathering dr-1 The Rising dr-3

The Rising dr-3 The Summoning dp-1

The Summoning dp-1 The Hunter And The Hunted

The Hunter And The Hunted Waking the Witch woto-11

Waking the Witch woto-11