- Home

- Kelley Armstrong

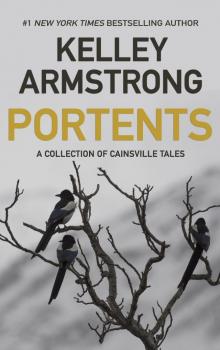

Portents

Portents Read online

Praise for Kelley Armstrong

“Armstrong is a talented and evocative writer who knows well how to balance the elements of good, suspenseful fiction, and her stories evoke poignancy, action, humor and suspense.”

The Globe and Mail

* * *

“[A] master of crime thrillers.”

Kirkus

* * *

“Kelley Armstrong is one of the purest storytellers Canada has produced in a long while.”

National Post

* * *

“Kelley Armstrong is one of my favorite writers.”

Karin Slaughter

* * *

“Armstrong is a talented and original writer whose inventiveness and sense of the bizarre is arresting.”

London Free Press

* * *

“Armstrong’s name is synonymous with great storytelling.”

Suspense Magazine

* * *

“Like Stephen King, who manages an under-the-covers, flashlight-in-face kind of storytelling without sounding ridiculous, Armstrong not only writes interesting page-turners, she has also achieved that unlikely goal, what all writers strive for: a genre of her own.”

The Walrus

Also by Kelley Armstrong

Cainsville series

Omens

Visions

Deceptions

Betrayals

Rituals

* * *

Aftermath

Missing

The Masked Truth

* * *

Rockton series

Otherworld series

Nadia Stafford trilogy

* * *

Age of Legends trilogy

Darkness Rising trilogy

Darkest Powers trilogy

Portents

A Collection of Cainsville Tales

Kelley Armstrong

Contents

Author’s Note

The Screams of Dragons

Devil May Care

Gabriel’s Gargoyles

The Orange Cat

Bad Publicity

Matagot

Lady of the Lake

Lost Souls excerpt

Rough Justice excerpt

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is purely coincidental.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without the written permission of the Author, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

* * *

Copyright © 2018 KLA Fricke Inc.

All rights reserved.

* * *

Cover image: Tahir’s Photography/Shutterstock

* * *

ISBN-13 (print): 978-1-989046-03-6

ISBN-13 (ebook): 978-1-989046-04-3

Author’s Note

The book series for Cainsville may have ended with Rituals, but the stories didn’t stop there. I had so much fun with that world that I started writing short fiction for it right from the start. By the time I got to Rituals, I had a full book’s worth of short fiction, which meant it was time to gather them together into a single volume.

We start with “The Screams of Dragons,” taking place when Rose was still a child and Seanna barely a toddler. This story was originally published in Subterranean Press Magazine and went on to several reprints.

From there, we fast forward to Seanna as a teen, for “Devil May Care,” told from Patrick’s point of view, as he unwittingly becomes a father.

Next we get a couple of stories about Seanna and Patrick’s son, Gabriel Walsh. Gabriel narrates “Gabriel’s Gargoyles” and “The Orange Cat.” The latter is based on Poe’s “The Black Cat” and was originally published in Nevermore.

“Bad Publicity” is another Patrick prequel and was featured in my Betrayals pre-order bonus.

Next comes a brand-new tale for all the readers who wanted to know more about Olivia’s cat, TC. “Matagot” takes place during the events of Visions, when TC was captured. The story delves into his origins.

“Lady of the Lake” is a novella, also written for the Betrayals preorder bonus. It’s set just after Deceptions, when Olivia and Ricky take off for a much-needed vacation in Cape Breton.

If you’re looking for more Cainsville, I’m still writing novellas in this world. You’ll find the first chapters of “Lost Souls” and “Rough Justice” at the back of this collection.

The Screams of Dragons

“And the second plague that is in thy dominion, behold it is a dragon. And another dragon of a foreign race is fighting with it, and striving to overcome it. And therefore does your dragon make a fearful outcry.”

—Cyfranc Lludd a Llefelys, translated by Lady Charlotte Guest

When he was young, other children talked of their dreams, of candy-floss mountains and puppies that talked and long-lost relatives bearing new bicycles and purses filled with crisp dollar bills. Bobby did not have those dreams. His nights were filled with golden castles and endless meadows and the screams of dragons.

The castles and the meadows came unbidden, beginning when he was too young to know what a castle or a meadow was, but in his dreams he’d race through them, endlessly playing, endlessly laughing. And then he’d wake to his cold, dark room, stinking of piss and sour milk, and he’d roar with rage and frustration. Even when he stopped, the cries were replaced by sulking, aggrieved silence. Never laughter. He only laughed in his dreams. Only played in his dreams. Only was happy in his dreams.

The dragons came later.

He presumed he’d first heard the story of the dragons in Cainsville. Visits to family there were the high points of his young life. While Cainsville had no golden castles or endless meadows, the fields and the forests, the spires and the gargoyles reminded him of his dreams, and calmed him and made him, if not happy, at least content.

They treated him differently in Cainsville, too. He was special there. A pampered little prince, his mother would say, shaking her head. The local elders paid attention to him, listened to him, sought him out. Better still, they did not do the same to his sister, Natalie. The Gnat, he called her—constantly buzzing about, useless and pestering. At home, she was the pampered one. His parents never seemed to know what to make of him, his discontent and his silences, and so they showered his bouncing, giggling little sister with double the love, double the attention.

In Cainsville the old people told him stories. Of King Arthur’s court, they said, but when he looked up their tales later, they were not quite the same. Theirs were stories of knights and magic, but lions too, and giants and faeries and, sometimes, dragons. That was why he was certain they’d told him this particular tale, even if he could not remember the exact circumstances. It was about a British king beset by three plagues. One was a race of people who could hear everything he said. The second was disappearing foodstuffs and impending starvation. The third was a terrible scream that turned out to be two dragons, fighting. And that was when he began to dream of the screams of dragons.

He did not actually hear the screams. He could not imagine such a thing, because he had no idea what a dragon’s scream would sound like. He asked his parents and his grandmother and even his Sunday school teacher, but they didn’t seem to understand the question. Even at night, his sleep was often filled with nothing but his small self, racing here and there, searching for the screams of dragons. He would ask and he would ask, but no one could ever tell him.

When he was almost eight, his grandmother noticed his sleepless nights. She asked

what was wrong, and he knew better than to talk about the dragons, but he began to think maybe he should tell her of the other dreams, the ones of golden palaces and endless meadows. One night, when his parents were out, he waited until the Gnat fell asleep. Then he padded into the living room, the feet on his sleeper whispering against the floor. His grandmother didn’t notice at first—she was too busy watching The Dick Van Dyke Show. He couldn’t understand the fascination with television. The moving pictures were dull gray, the laughter harsh and fake. He supposed they were for those who didn’t dream of gold and green, of sunlight and music.

He walked up beside her. He did not sneak or creep, but she was so absorbed in her show that when he appeared at her shoulder, she shrieked and in her face, he saw something he’d never seen before. Fear. It fascinated him, and he stared at it, even as she relaxed and said, “Bobby? You gave me quite a start. What’s wrong, dear?”

“I can’t sleep,” he said. “I have dreams.”

“Bad dreams?”

He shook his head. “Good ones.”

Her old face creased in a frown. “And they keep you awake?”

“No,” he said. “They make me sad.”

She clucked and pulled him onto the chair, tucking him in beside her. “Tell Gran all about them.”

He did, and as he talked, he saw that look return. The fear. He decided he must be mistaken. He hadn’t mentioned the dragons. The rest was wondrous and good. Yet the more he talked, the more frightened she became, until finally she pushed him from the chair and said, “It’s time for bed.”

“What’s wrong?”

She said, “Nothing,” but her look said something was very, very wrong.

For the next few weeks, his grandmother was a hawk, circling him endlessly, occasionally swooping down and snatching him up in her claws. Most times, she avoided him directly, though he’d catch her watching him. Studying him. Scrutinizing him. Once they were alone in the house, she’d swoop. She’d interrogate him about the dreams, unearthing every last detail, even the ones he thought he’d forgotten.

On the nights when his parents were gone, she insisted on drawing his baths, adding in some liquid from a bottle and making the baths so hot they scalded him and when he cried, she seemed satisfied. Satisfied and a little frightened.

The strangest of all came nearly a month after he’d told her of the dreams. She’d made stew for dinner and she served it in eggshells. When she brought them to the table, the Gnat laughed in delight.

“That’s funny,” she said. “They’re so cute, Gran.”

His grandmother only nodded absently at the Gnat. Her watery blue eyes were fixed on him.

“What do you think of it, Bobby?” she asked.

“I . . .” He stared at the egg, propped up in a little juice glass, the brown stew steaming inside the shell. “I don’t understand. Why is it in an egg?”

“For fun, dummy.” His sister shook her head at their grandmother. “Bobby’s never fun.” She pulled a face at him. “Boring Bobby.”

His grandmother shushed her, gaze still on him. “You think it’s strange.”

“It is,” he said.

“Have you ever seen anything like this before?”

“No.”

She waited, as if expecting more. Then she prompted, “You would say, then, that you’ve never, in all your years, seen something like this.”

It seemed an odd way to word it, but he nodded.

And with that, finally, she seemed satisfied. She plunked down into her chair, exhaling, before turning to him and saying, “Go to your room. I don’t want to see you until morning.”

He glanced up, startled. “What did I—?”

“To your room. You aren’t one of us. I’ll not have you eat with us. Now off with you.”

He pushed his chair back and slowly rose to his feet.

The Gnat stuck out her tongue when their grandmother wasn’t looking. “Can I have his egg?”

“Of course, dear,” Gran said as he shuffled from the kitchen.

The next morning, instead of going to school, his grandmother took him to church. It was not Sunday. It was not even Friday. As soon as he saw the spires of the cathedral, he began to shake. He’d done something wrong, horribly wrong. He’d lain awake half the night trying to figure out what he could have done to deserve bed without dinner, but there was nothing. She’d fed him stew in an eggshell and, while perplexed, he had still been very polite and respectful about it.

The trouble had started with telling her about the dreams, but who could find fault with tales of castles and meadows, music and laughter?

Perhaps she was going senile. It had happened to an old man down the street. They’d found him in their yard, wearing a diaper and asking about his wife, who’d died years ago. If that had happened to his grandmother, Father Joseph would see it.

Certainly, he seemed to, given the expression on Father Joseph’s face after Gran talked to him alone in the priest’s office. Father Joseph emerged as if in a trance, and Gran had to direct him to the pew where Bobby waited.

“See?” she said, waving her hand at Bobby.

The priest looked straight at him, but seemed lost in his thoughts. “No, I’m afraid I don’t, Mrs. Sheehan.”

Gran’s voice snapped with impatience. “It’s obvious he’s not ours. Neither his mother nor his father nor any of his grandparents have blond hair. Or dark eyes.”

Sweat beaded on the priest’s forehead and he tugged his collar. “True, but children do not always resemble their parents, for a variety of reasons, none of them laying any blame at the foot of the child.”

“Are you suggesting my daughter-in-law was unfaithful?”

Father Joseph’s eyes widened. “No, of course not. But the ways of genetics—like the ways of God—are not always knowable. Your daughter-in-law does have light hair, and I believe she has a brother who is blond. If my recollection of science is correct, dark eyes are the dominant type, and I’m quite certain if you searched the family tree beyond parents and grandparents you would find your answer.”

“I have my answer,” she said, straightening. “He is a changeling.”

Two drops of sweat burst simultaneously and dribbled down the priest’s face. “I . . . I do not wish to question your beliefs, Mrs. Sheehan. I know such folk wisdom is common in the . . . more rural regions of your homeland—”

“Because it is wisdom. Forgotten wisdom. I’ve tested him, Father. I gave him dinner in an eggshell, as I explained.”

“Yes, but . . .” The priest snuck a glance around, as if hoping for divine intervention—or a needy parishioner to stumble in, requiring his immediate attention. “I know that is the custom, but I cannot say I rightly understand it.”

“What is there to understand?” She put her hands on her narrow hips. “It’s a test. I gave him stew in eggshells, and he said he’d never seen anything like it. That’s what a changeling will say.”

“I beg your pardon, ma’am, but I believe that’s what anyone would say, if given their meal served in an egg.”

She glowered at him. “I put him in a tub with foxglove, too, and he became ill.”

“Foxglove?” The priest’s eyes rounded again. “Is that not a poison?”

“It is if you’re a changeling. I also gave him one of my heart pills, because it’s made from digitalis, which is also foxglove. My pill made him sick.”

“You gave . . .” For the first time since he’d come in, Father Joseph looked at Bobby, really looked at him. “You gave your grandson your heart medication? That could kill a boy—”

“He isn’t a boy. He’s one of the Fair Folk.” Gran met Bobby’s gaze. “An abomination.”

Now Father Joseph’s face flushed, his eyes snapping. “No, he is a child. You will not speak of him that way, certainly not in front of him. I’m trying to be respectful, Mrs. Sheehan. You are entitled to your superstitions and folksy tales, but not if they involve poisoning an innocent child.” He knelt in f

ront of Bobby. “You’re going to come into my office now, son, and we’ll call your parents. Is your mother at work?”

He nodded.

“Do you know the number?”

He nodded again.

The priest took Bobby’s hand and, without another word, led him away as his grandmother watched, her eyes narrowing.

That was the beginning of “the bad time,” as his parents called it, whispered words, even years later, their eyes downcast, as if in shame. The situation did not end with that visit to the priest. His grandmother would not drop the accusation. He was a changeling. A faerie child dropped into their care, her real grandson spirited away by the Fair Folk. Finally, his parents broke down and asked the priest to perform some ritual—any ritual—to calm his grandmother’s nerves. The priest refused. To do so would be to lend credence to the preposterous accusation and could permanently scar the child’s psyche.

The fight continued. He heard his parents talking late at night about the shame, the great shame of it all. They were intelligent, educated people. His father was a scientist, his mother the lead secretary in her firm. They were not ignorant peasants, and it angered them that Father Joseph didn’t understand what they were asking—not to “fix” their son but simply to pretend to, for the harmony of the household.

The Calling

The Calling Darkest Powers Bonus Pack

Darkest Powers Bonus Pack Betrayals

Betrayals Sea of Shadows

Sea of Shadows Rough Justice

Rough Justice This Fallen Prey

This Fallen Prey City of the Lost: Part Five

City of the Lost: Part Five Perfect Victim

Perfect Victim Dime Store Magic

Dime Store Magic Personal Demon

Personal Demon Haunted

Haunted Living With the Dead

Living With the Dead Visions

Visions The Summoning

The Summoning Broken

Broken City of the Lost: Part One

City of the Lost: Part One No Humans Involved

No Humans Involved The Awakening

The Awakening The Reckoning

The Reckoning The Gathering

The Gathering Bitten

Bitten Thirteen

Thirteen Gifted

Gifted The Orange Cat and Other Cainsville Tales

The Orange Cat and Other Cainsville Tales Darkest Powers Bonus Pack 2

Darkest Powers Bonus Pack 2 Rituals

Rituals Waking the Witch

Waking the Witch Made to Be Broken

Made to Be Broken Lost Souls

Lost Souls Empire of Night

Empire of Night Wild Justice

Wild Justice Double Play

Double Play Alone in the Wild

Alone in the Wild City of the Lost: Part Two

City of the Lost: Part Two A Stranger in Town

A Stranger in Town Watcher in the Woods: A Rockton Novel

Watcher in the Woods: A Rockton Novel Atoning

Atoning Spellbound

Spellbound Wolf's Bane

Wolf's Bane A Darkness Absolute

A Darkness Absolute Ballgowns & Butterflies: A Stitch in Time Holiday Novella

Ballgowns & Butterflies: A Stitch in Time Holiday Novella Wherever She Goes

Wherever She Goes A Royal Guide to Monster Slaying

A Royal Guide to Monster Slaying Life Is Short and Then You Die

Life Is Short and Then You Die City of the Lost: Part Three

City of the Lost: Part Three Frostbitten

Frostbitten A Stitch in Time

A Stitch in Time Industrial Magic

Industrial Magic Wherever She Goes (ARC)

Wherever She Goes (ARC) Snowstorms & Sleigh Bells: A Stitch in Time holiday novella

Snowstorms & Sleigh Bells: A Stitch in Time holiday novella Exit Strategy

Exit Strategy Forest of Ruin

Forest of Ruin Cursed Luck, Book 1

Cursed Luck, Book 1 The Gryphon's Lair

The Gryphon's Lair City of the Lost

City of the Lost City of the Lost: Part Four

City of the Lost: Part Four Deceptions

Deceptions City of the Lost: Part Six

City of the Lost: Part Six Urban Enemies

Urban Enemies Stolen

Stolen Every Step She Takes

Every Step She Takes Portents

Portents Wolf's Curse

Wolf's Curse The Unquiet past

The Unquiet past Omens ct-1

Omens ct-1 Cruel Fate

Cruel Fate The Calling dr-2

The Calling dr-2 The Awakening dp-2

The Awakening dp-2 Life Is Short and Then You Die_First Encounters With Murder From Mystery Writers of America

Life Is Short and Then You Die_First Encounters With Murder From Mystery Writers of America Goddess of Summer Love: a Cursed Luck novella

Goddess of Summer Love: a Cursed Luck novella Strangers Among Us

Strangers Among Us The Gathering dr-1

The Gathering dr-1 The Rising dr-3

The Rising dr-3 The Summoning dp-1

The Summoning dp-1 The Hunter And The Hunted

The Hunter And The Hunted Waking the Witch woto-11

Waking the Witch woto-11