- Home

- Kelley Armstrong

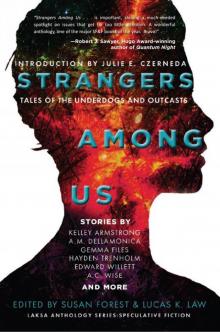

Strangers Among Us

Strangers Among Us Read online

STRANGERS

AMONG

US

TALES OF THE UNDERDOGS AND OUTCASTS

LAKSA ANTHOLOGY SERIES: SPECULATIVE FICTION

Edited by Susan Forest & Lucas K. Law

LAKSA MEDIA GROUPS INC.

www.laksamedia.com

Strangers Among Us: Tales of the Underdogs and Outcasts

Laksa Anthology Series: Speculative Fiction

Copyright © 2016 by Susan Forest and Lucas K. Law

All rights reserved

This book is a work of fiction. Characters, names, organizations, places and incidents portrayed in these stories are either products of the authors’ imaginations or are used fictitiously, and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual situations, events, locales, organizations, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Laksa Media Groups supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Laksa Media Groups to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Strangers among us : tales of the underdogs and outcasts / edited

by Susan Forest and Lucas K. Law ; [introduction by Julie E. Czerneda].

(Laksa anthology series: speculative fiction)

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-9939696-0-7 (paperback).—ISBN 978-0-9939696-4-5 (bound).—

ISBN 978-0-9939696-2-1 (pdf).—ISBN 978-0-9939696-1-4 (epub).—

ISBN 978-0-9939696-3-8 (kindle)

1. Science fiction, Canadian (English). 2. Fantasy fiction, Canadian (English).

3. Speculative fiction, Canadian (English). 4. Mental health—Fiction. .Mental illness—

Fiction. I. Forest, Susan, editor II. Law, Lucas K., editor

PS8323.S3S77 2016 C813’.0876208353 C2015-907597-1

C2015-907598-X

LAKSA MEDIA GROUPS INC.

Calgary, Alberta, Canada

www.laksamedia.com

[email protected]

Edited by Susan Forest and Lucas K. Law

Cover and Interior Design by Samantha M. Beiko

FIRST EDITION

Susan Forest

To my parents,

Don and Peggy Forest,

Who shared with me their love of stories.

Lucas K. Law

To my parents,

Leonard & Florence Law,

For the joy of reading and love of libraries;

To my partner,

Tim H. Feist,

For the continuing support and love;

In memory of

Marilyn Lewis-Steer,

Who challenged me to tackle this anthology project

(instead of talking about it).

CONTENTS

FOREWORD - Lucas K. Law

INTRODUCTION - Julie E. Czerneda

The Culling - Kelley Armstrong

Dallas’s Booth - Suzanne Church

What Harm - Amanda Sun

How Objects Behave on the Edge of a Black Hole - A.C. Wise

Washing Lady’s Hair - Ursula Pflug

The Weeds and the Wildness - Tyler Keevil

Living in Oz - Bev Geddes

I Count the Lights - Edward Willett

The Dog and the Sleepwalker - James Alan Gardner

Carnivores - Rich Larson

Tribes - A.M. Dellamonica

Troubles - Sherry Peters

Frog Song - Erika Holt

Wrath of Gaia - Mahtab Narsimhan

Songbun - Derwin Mak

What You See (When the Lights Are Out) - Gemma Files

The Age of Miracles - Robert Runté

Marion’s War - Hayden Trenholm

The Intersection - Lorina Stephens

AFTERWORD - Susan Forest

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS

ABOUT THE EDITORS

COPYRIGHT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

APPENDIX: MENTAL HEALTH RESOURCES

FOREWORD

Lucas K. Law

My family loves to read newspapers, books and magazines, regardless of category or genre; reading, or rather, the quest for knowledge and information, must be etched in our genetic make-up. So, it isn’t a surprise that the public library was my favourite childhood haunt. I was constantly flooded by my over-active imagination; I chatted with my imaginary friends, making plans, dreaming ideas and telling stories.

And let’s not forget food, the cradle of my family’s gatherings and kitchen conversations, constant in motion throughout my life: for, through stories, our mother’s home-cooked meals offered a window into our past, present and future.

What do reading, imaginary playmates, and clan gatherings have in common to this book you are holding?

Family and friends, creativity and story.

All of us have special memories and favourite stories in our kin traditions, which we often share, even with strangers. But, for some of us, buried beneath those wonderful connections lurk secrets, fears and self-doubts. We wear masks to hide, shade or guard our shame and loneliness. Sometimes, we do it so well, even our loved ones have no clue about our misery, struggle and depression.

For some, family support provides enough strength to allow them to overcome their struggles and challenges in a positive way. Others are not as fortunate. They watch their lives crumble away, layer by layer, piece by piece.

Each of us has a story to tell. In the last few years, several of my relatives and friends have been struck with mental illness. I have seen their isolation, fear, confusion, job losses, insecurity, and anxiety. Mental illness continues to be burdened by stigma, and despite loving support, often those affected still have difficulty asking for help or talking about their experiences without feeling guilt and shame.

The idea for this anthology germinated as I was struck by the thinness of the line between mental health and mental illness. Mental illness can target any age group at any time. Mental illness can afflict a person for a period of time or become a life-long struggle. Mental illness can spring from many sources and manifest in many forms.

In this anthology, Julie E. Czerneda and nineteen authors come together to show their support for mental health through the written word. Susan and I are grateful for their Tales of the Underdogs and Outcasts, for the glimpses we are given into these fictional lives warn us not to underestimate the underdogs and outcasts: they have the resources to teach or save the world.

This book is for a special friend and fellow writer, Marilyn Lewis-Steer, who passed away on May 28, 2015, after a valiant battle with cancer. She gave me the inspiration and mental adjustment I needed to begin this work. I will always remember Marilyn for her kind words, her belief in lifelong education, her support for volunteerism—to pay forward and give back. To her, I needed . . . I wanted to say a final thank-you. This one is for you, Marilyn.

Please promote mental health and support your local charitable organizations. A portion of this anthology’s net revenue will go to support the Canadian Mental Health Association.

—Lucas K. Law, Calgary and Qualicum Beach, 2016

INTRODUCTION

Julie E. Czerneda

Who are strangers?

People we don’t yet know. We spot them, cued to their difference from the familiar-to-us by their look, by how they walk or talk or dress. We prepare for each new encounter, for you never know—do you?—with strangers.

Strangers. The harried mother who spares a fleeting

smile . . . the tattooed boarder who gallantly holds the door . . . the executive bickering with thin air . . . the teen moving to music only she can hear . . . the blue-faced football fan who weaves and waves to everyone around.

Strangers. The child who doesn’t meet your eye or smile back . . . the ancient who rocks and spits . . . the man who stalks by, swearing at passing cars . . . the huddled silent shape in a doorway, eyes fixed on air.

Strangers.

Our reaction, of course, depends on many things: the situation, our experience and expectations, how they seem to us at first glance. It’s instinctive and often necessary to make a snap judgment: ignore, avoid, or greet. We don’t come tagged with our inner truths. We can’t tell by looking if that angry-looking stranger is angry at us—

Or at something only she can see.

Scary either way, isn’t it? Such a disquieting awareness, that the mind can be ill. We know what to do about gashed skin or child’s fever. We can see for ourselves when a wound is healed or a child is over a flu. The mind though. It’s secretive, complex, powerful. When it’s sick, we flinch, not knowing what to do, unable to see. There’s nothing familiar to guide us.

Which is why stories like the ones gathered in this astonishing anthology are important. They put us inside the heads of strangers. They make us feel those inner truths. What is it like to be angry or afraid, to hear voices, to be unable to relate to another human being, to struggle and slip and struggle and wish—above all—to be understood. To strive when it’s our minds—not crippled limbs or other ills of the flesh—that betray and hobble us. To do our best when society, family, friends ignore or dismiss us.

To triumph, as in these stories, despite that terrible solitude. Or . . . because of it.

As with any encounter, there’s the chance you’ll meet a stranger here who proves familiar; maybe someone you already know. Maybe yourself.

If you do, toss away experience and expectation. Ignore the differences. Dismiss pity and any preconception of weakness.

Instead see the potential. Feel the passion.

For we are all strangers to one another, locked inside our minds, healthy or not quite. We’re each the unique sum of advantage, disadvantage, and living with both. As you read these imaginative, original stories, you’ll discover what matters most of all:

What we choose to be.

—Julie E. Czerneda, Severn, 2016

Author of The Clan Chronicles from DAW Books

THE CULLING

Kelley Armstrong

We grew up with stories of how the Cullings saved us. Stories of the famines and the aftermath, a world that once grew grain and corn in abundance, the forests overrun with rabbits and deer, lakes and streams brimming with trout and salmon. How all that had come to an end, the water drying up and everything dying with the drought—the grain and the corn and the rabbits and the deer and the trout and the salmon. And us. Most of all, us.

Left with so few resources, it was not enough to simply ration food and water. Not enough to reduce birth rates. Not enough to refuse any measures to prevent death. We needed more. We needed the Cullings.

The Cullings removed surplus population by systematically rooting out “weakness.” At first, they targeted the old and infirm. When that was no longer enough, any physical disability could see one culled. Even something that did not impair one’s ability to work—like a disfiguring birthmark—was said to be enough, on the reasoning that there was a taint in the bloodline that might eventually lead to a more debilitating condition.

The population dropped, but so did the water supply, and with it, the food supply, and eventually more stringent measures were required. That’s when they began targeting anyone who was different, in body or in mind. If you kept too much to yourself, rejecting the companionship of others; if you were easily upset or made anxious or sad; if you occasionally saw or heard things that weren’t there . . . all were reasons to be culled. But the thing is, sometimes those conditions are easier to hide than a bad leg or a mark on your face. It just takes a little ingenuity and a family unwilling to let you go.

“Who are you talking to, Marisol?” my mother says as she hurries into my room.

I motion to my open window, and to Enya, who had stopped to chat on her way to market. She says a quick hello to my mother and then a goodbye to me before carrying on down the village lane.

I murmur to my mother, “A real, living friend. You can see her, too, right?”

“I was just—”

“Checking, I know.” I put my arm around her shoulders. Having just passed my sixteenth birthday, I’m already an inch taller and making the most of it. “I have not had imaginary friends in many years, Momma.”

“I know. It’s just . . . I’ve heard you talking recently. When you’re alone.”

“I argue with myself. You know how I am—always spoiling for a fight. If no one’s around to give me one, I must make do.” I smack a kiss on her cheek. “I don’t hear voices, Momma. I’m not your sister. I have a little of what she did, but only a little, and I know how to hide it. I don’t talk about my imaginary friends, even if they’re long gone. I don’t let anyone see my wild pictures. I don’t tell anyone my even wilder stories. I am absolutely, incredibly, boringly normal.”

She makes a face at me.

“What?” I say. “It is boring. But I will fake it, for you and Papa.”

“For you, Mari. Our worries are for you, and yours should be, too.”

“But I don’t need to be worried, because I am very careful.”

“The Culling is coming.”

“As you have reminded me every day for the past month. I will be fine. I’ll even stop arguing with myself, though that means you’ll need to break up more fights between Dieter and me.”

“Your brother will happily argue with you if it keeps you safe.”

“It will.” I give her a one-armed hug. “I’ll be fine, Momma.”

Liar, the voice whispers in my ear. I squeeze my eyes shut, force it back and steer my mother from my room.

I have heard whispers that the Culling will be worse this year. Rumours say one of our two wells is running dry. The man who started the talk was a runner, one of those who carted the wheeled barrels from the well. The council called him a liar and a traitor. Said he’d been paid by another town to sow dissent. They executed him in the village square. But that hasn’t stopped the rumours. If the well is drying up, this will indeed be a terrible Culling. And I must be prepared.

I do what I always do when I need a reminder. Because sometimes I do. There are nights and, yes, days, when the voice in my head says I shouldn’t be so careful. I shouldn’t need to be. That I should stand up and fight back. That I am a coward if I do not. But that is, I recognize, the sickness talking.

Fighting back is not an option. It absolutely is not, and it’s madness to think it could be. I must remember that my aunt was the same age as me when she was culled. I must not comfort myself with my parents’ insistence that my sickness is not as severe. Any defect—mental or physical—is cause for Culling.

I walk through the village square. At the far side is a wooden box, barely the height of an average person and even less wide. Inside is a man. He sits in the back corner, thin legs pulled in as he hums to himself. His hair is matted and filthy. His naked body reeks. We might not have the water to clean ourselves as we used to but we have adapted, and there is no excuse for this. No excuse other than that he does not care, is beyond caring, cannot even bring himself to let others run a damp rag over his skin.

He doesn’t just smell of old sweat. There’s the stench of urine and feces too. The notice beside his cage explains that he used to have a bucket, but it was taken away because the only use he made of it was to beat anyone who opened his door.

The man is here as a warning, lest we feel sympathy for something as harmless as talking to oneself. That was how his sickness started, the sign explains. As a boy who’d whispered to himself and then talked to

himself and then shouted at himself, and others and the voices in his head.

This is you, that voice in my own head whispers. This is what you’ll become—naked and stinking in a box.

I squeeze my eyes shut to silence it. It’s quiet most of the time, like the girl in the corner of the class who rarely speaks, and you can almost forget she’s there. Almost.

I come here to remind myself that she’s there—that voice, that sickness.

My parents say my aunt never hurt anyone, that her voices never commanded her to do anything worse than draw wild pictures, beautiful and haunting pictures that she’d sketch in charcoal on wood slabs, before scrubbing them clean to reuse. My parents kept the last one she did, before she was Culled, and sometimes I pull it out and lose myself in it, and I weep because I see so much in them. Because I understand them—the fancies and the dreams and the nightmares within them, equally horrifying and beautiful.

I come here to remind myself of what I must keep hidden. Of how hard I must work to hide it. For my sake. For my family’s sake.

Before I leave, I’ll whisper to him and slide food between the bars, and feel guilty as I do so, as if I’m treating him like an animal. But it is all I can do. Repayment for the lesson he provides.

“Marisol?” a voice says behind me, and I turn to see Enya, market basket over her arm. She covers her nose with her free hand. “What are you doing here?”

“Reminding myself,” I say.

Her brows rise. “Of what?”

“Of what the council protects us against. When the Culling comes, I will feel pity for those who only seem a little different and not at all dangerous. I’ll remind myself of that.” I point at the notice, which explains how he killed his entire family before being captured.

The Calling

The Calling Darkest Powers Bonus Pack

Darkest Powers Bonus Pack Betrayals

Betrayals Sea of Shadows

Sea of Shadows Rough Justice

Rough Justice This Fallen Prey

This Fallen Prey City of the Lost: Part Five

City of the Lost: Part Five Perfect Victim

Perfect Victim Dime Store Magic

Dime Store Magic Personal Demon

Personal Demon Haunted

Haunted Living With the Dead

Living With the Dead Visions

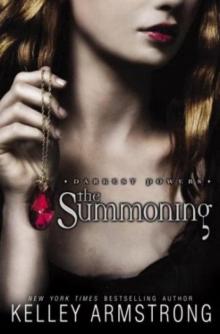

Visions The Summoning

The Summoning Broken

Broken City of the Lost: Part One

City of the Lost: Part One No Humans Involved

No Humans Involved The Awakening

The Awakening The Reckoning

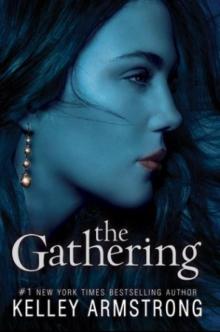

The Reckoning The Gathering

The Gathering Bitten

Bitten Thirteen

Thirteen Gifted

Gifted The Orange Cat and Other Cainsville Tales

The Orange Cat and Other Cainsville Tales Darkest Powers Bonus Pack 2

Darkest Powers Bonus Pack 2 Rituals

Rituals Waking the Witch

Waking the Witch Made to Be Broken

Made to Be Broken Lost Souls

Lost Souls Empire of Night

Empire of Night Wild Justice

Wild Justice Double Play

Double Play Alone in the Wild

Alone in the Wild City of the Lost: Part Two

City of the Lost: Part Two A Stranger in Town

A Stranger in Town Watcher in the Woods: A Rockton Novel

Watcher in the Woods: A Rockton Novel Atoning

Atoning Spellbound

Spellbound Wolf's Bane

Wolf's Bane A Darkness Absolute

A Darkness Absolute Ballgowns & Butterflies: A Stitch in Time Holiday Novella

Ballgowns & Butterflies: A Stitch in Time Holiday Novella Wherever She Goes

Wherever She Goes A Royal Guide to Monster Slaying

A Royal Guide to Monster Slaying Life Is Short and Then You Die

Life Is Short and Then You Die City of the Lost: Part Three

City of the Lost: Part Three Frostbitten

Frostbitten A Stitch in Time

A Stitch in Time Industrial Magic

Industrial Magic Wherever She Goes (ARC)

Wherever She Goes (ARC) Snowstorms & Sleigh Bells: A Stitch in Time holiday novella

Snowstorms & Sleigh Bells: A Stitch in Time holiday novella Exit Strategy

Exit Strategy Forest of Ruin

Forest of Ruin Cursed Luck, Book 1

Cursed Luck, Book 1 The Gryphon's Lair

The Gryphon's Lair City of the Lost

City of the Lost City of the Lost: Part Four

City of the Lost: Part Four Deceptions

Deceptions City of the Lost: Part Six

City of the Lost: Part Six Urban Enemies

Urban Enemies Stolen

Stolen Every Step She Takes

Every Step She Takes Portents

Portents Wolf's Curse

Wolf's Curse The Unquiet past

The Unquiet past Omens ct-1

Omens ct-1 Cruel Fate

Cruel Fate The Calling dr-2

The Calling dr-2 The Awakening dp-2

The Awakening dp-2 Life Is Short and Then You Die_First Encounters With Murder From Mystery Writers of America

Life Is Short and Then You Die_First Encounters With Murder From Mystery Writers of America Goddess of Summer Love: a Cursed Luck novella

Goddess of Summer Love: a Cursed Luck novella Strangers Among Us

Strangers Among Us The Gathering dr-1

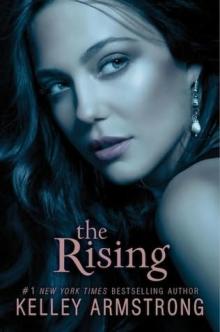

The Gathering dr-1 The Rising dr-3

The Rising dr-3 The Summoning dp-1

The Summoning dp-1 The Hunter And The Hunted

The Hunter And The Hunted Waking the Witch woto-11

Waking the Witch woto-11